Chapter 1 excerpt

The American Nation-building Creed

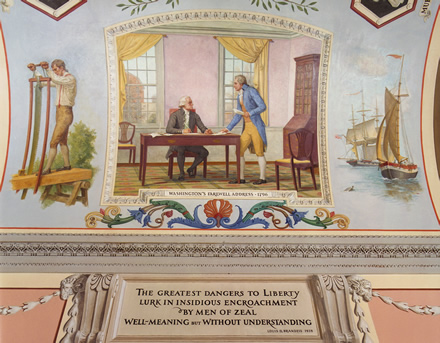

The painting at the U.S. Capitol building shows Alexander Hamilton helping Washington to draft his address. George Washington's Farewell Address (1796) envisioned an evolving international society of states, where the American nation-building model would remain separate but broadly influential. Credit: Washington's Farewell Address, 1796. Allyn Cox, Architect of the Capitol

Click to enlarge photo.

American society has never lacked ambition.

American society has never lacked ambition.

During the last

two centuries the global reach of the United States has spread

like rushing water, moving with ever-greater speed across the

landscape, around barriers, and into the nooks and crannies of what

were once distant locales. This dynamic dispersion of U.S. influence

shows no sign of stopping in the 21st century. In recent years

the nation's soldiers, treasure, and social media have expanded into

Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, and other places Shakespeare

described as "monstrous," "desolate," and largely inhospitable to foreign

occupiers.

Shakespeare never visited the exotic lands of his plays, but Americans

have prodigiously trod in what the playwright called the "mudded"

terrains. The growing presence of the United States in these regions

transformed the applications of the country's power beyond the

dreams of the Founding Fathers.

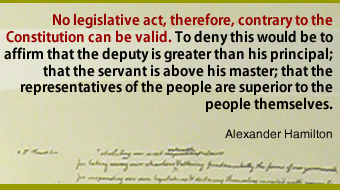

James Madison, Alexander Hamilton,

and their many contemporaries could never have imagined that their

new nation would one day dominate all the oceans of the globe, with

permanent military bases in more than fifty countries. Compared to its

most powerful predecessors in Europe and Asia since the Middle Ages,

the United States became a much larger and heavier global presence.

"Soft" cultural power was both a product and a producer of America's

unprecedented "hard" economic and military might.

The Ever-Lasting Revolution

Despite the nation's extraordinary growth, the early assumptions of

American power remained fundamentally unchanged over more than

two centuries.

Basic ideas about politics transferred with consistency

from generation to generation, and from territory to territory. The

image of the American Revolution, and the founding of a new nation

and a new government at the time, framed all

future discussions in the United States about how to live with other societies.

The Revolution was an experience, a myth, and also a paradigm for defining

political mission.

Nothing could exemplify this point more than the American reaction

to the horrible terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. Amidst

the smoking remains of New York's World Trade Center, President

George W. Bush memorably announced that "America today is on

bended knee in prayer" for its people and its principles. In a two-minute

pep talk to tired rescue workers he used the word "nation"

four times, along with a flag that he proudly waved, to affirm American

unity and power in the intrepid defense of individual liberty.

Appearing before Congress less than a week later, the president spoke

in revolutionary terms: "this country will define our times, not be defined

by them. As long as the United States of America is determined this country will define our times, not be defined by them. As long as the United States of America is determined and strong, this will not be an age of terror. This will be an age of liberty here and across the world."

This chapter examines the origins of a specific and enduring approach to nation-building that has guided American thinking and action for more than 200 years. Nation-building is a long-standing American vision, a common PURPOSE across centuries.

Click to learn more about the 5 "P"s of nation-building.