Introduction excerpt

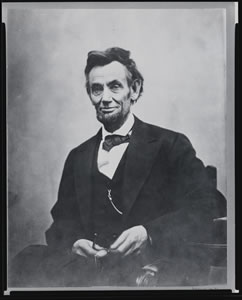

President Abraham Lincoln's Union program imposed the American nation-building creed on the former Confederacy, transforming the slave-holding region into part of a representative free labor society. Reconstruction marked the slow and incomplete, but still unprecedented, beginning of nation-building in the American South. Credit: Abraham Lincoln, 1965, Alexander Gardner, Library of Congress.

to 'Liberty's Surest Guardian'

When George Washington wrote of an American "Union"

with "a government for the whole," his vision was radical,

perhaps foolhardy. Such a thing had never existed among

a diverse people, across a vast continent, with no established royal or

military authority.

When George Washington wrote of an American "Union"

with "a government for the whole," his vision was radical,

perhaps foolhardy. Such a thing had never existed among

a diverse people, across a vast continent, with no established royal or

military authority.

The Union of politically empowered citizens that

Washington described was an aspiration more than a reality. It was a

dream after two difficult decades of revolution, war, and reconstruction.

Washington's vision was prophetic. He was ahead of his times.

His contemporaries, especially in Europe, expected tyranny, anarchy,

or the return of foreign empire in North America after the British

defeat. Eighteenth-century thinkers had few models of a good government

"with powers properly distributed and adjusted." They had

even fewer models of a strong government that became a "guardian"

rather than an oppressor of liberty.

George Washington's 18th-century radicalism evolved into

the 21st century's conventional wisdom. The success of the

American experiment in building a prosperous and democratic Union

discredited other options. When Washington wrote his words people

advocated many kinds of government: monarchy, theocracy, confederation,

empire, city-state, and even small republic.

The new standard

Representative government for a large, diverse, and united population living in a

dispersed but discrete territory—that became the contemporary standard

for the modern "nation-state." It was almost nonexistent during

Washington's lifetime. In its early American formation, the political

institutions that we now take for granted were an eccentric experiment—

an "exception" to the common arrangements of the era.

Click to learn more about the 5 "P"s of nation-building.

This chapter introduces the concept of nation-building as a PROCESS that is both historical and contemporary.

Two hundred years after Washington, American exceptionalism

became the normal expectation for citizens. The United States proved

that large, diverse, and united societies—"nations"—could achieve

more than their fragmented counterparts. The United States also

showed that the first president's claims about the

virtues of a representative

government were well founded. A powerful government of the

people did more for the people, and it was generally more stable than

its predecessors.

The American model stood out

for its unity and its representativeness. Although many Americans—

including women, African Americans, and others—did not initially have full rights of

citizenship, the society they inhabited encouraged more popular participation

in politics than any late-18th- or 19th-century

counterpart. Politics was part of the nation's common culture. The

state birthed from rallies, debates, and conflicts claimed legitimacy

from its roots in the street, not the gentleman's club.

By the 20th century virtually all governments organized

themselves as nation-states. Dominant state institutions claimed legitimacy

because they spoke for the people—not divine authority or

a borderless ethnicity—in a particular place.

Modern political power

was nation-state power.