Chapter 3 excerpt

Philippines: Reconstruction after empire

In the last year of the 19th century the United States quickly

became a major nation-builder in Asia. No one, not even the

most aggressive promoters of expansion, had planned for this. No

one, not even the most prescient policy-planners, was prepared for

the new challenges.

In the last year of the 19th century the United States quickly

became a major nation-builder in Asia. No one, not even the

most aggressive promoters of expansion, had planned for this. No

one, not even the most prescient policy-planners, was prepared for

the new challenges.

Wrested from Spanish control by American military forces and

local revolutionaries, the Philippines included more than 7,000 islands inhabited by more than 7 million people, 8,000 miles from Washington, D.C. The United States had no

experience exercising political authority in such a setting. Since its

founding, and especially through the Civil War, the United States had

built an effective continental state with powerful, but still limited,

extensions of influence into other parts of the Western Hemisphere.

Nineteenth-century American nation-building was continental and

hemispheric, not global.

Opposing views of reconstruction

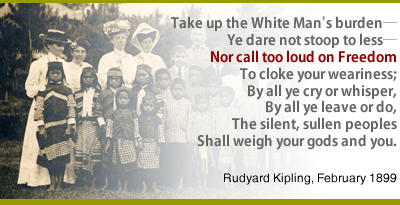

Many Americans wanted things to stay that way. Prominent figures—

including congressmen, religious leaders, intellectuals, and

businesspeople—opposed what they viewed as a misguided urge for

American "imperialism."

Asia offered economic promise, but it was

unrealized. Asia was alluring in its exoticism, but it was also impenetrable

in its cultural and racial complexity. Most of all, Asia was very

far away. How could Americans imagine that their ideas about sovereignty,

territory, and government would transfer across the vast Pacific

Ocean? Even if some of these ideas did travel, how could Americans

ever hope to manage their application by sail and steamship, 8,000 miles from home?

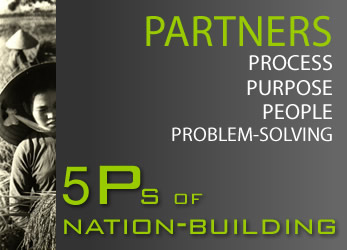

Click to learn more about the 5 "P"s of nation-building.

This chapter investigates American nation-building efforts in the Philippines following the defeat of the Spanish colonial empire. American efforts in the Philippines relied on PARTNERSHIPS with many local figures.

During the four decades of American occupation in the Philippines,

the United States remained uncertain, unprepared, and deeply

divided about its policies. There never was an American consensus on

the Philippines. Instead, there was broad agreement about what the

United States would not do.

Americans would not build a large standing military force to flex their muscles in Asia. The United States Army and Navy remained very small in comparison to their peers and their potential capabilities. Military doctrine continued to emphasize continental defense and harbor fortifications, not preparation for battle far from home. Grading the quality of the troops, the procurement of equipment, and the planning for conflict, American forces in the early 20th century were “less prepared for war” than in decades past. The poor state of the U.S. military on the eve of the First World War made this evident to everyone, particularly those who remembered the much larger, better organized, and battle-hardened Union Army of a generation earlier.

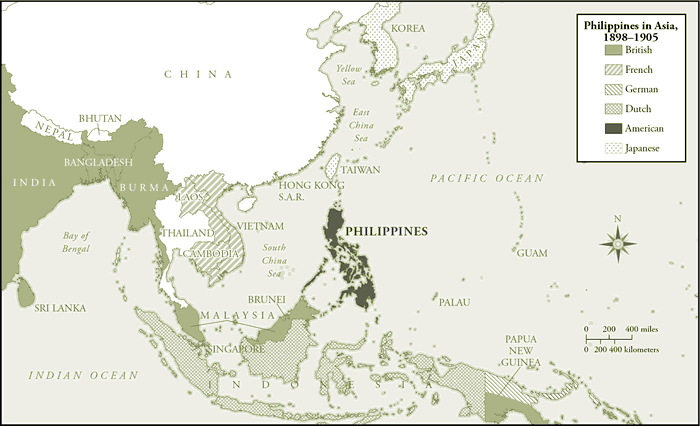

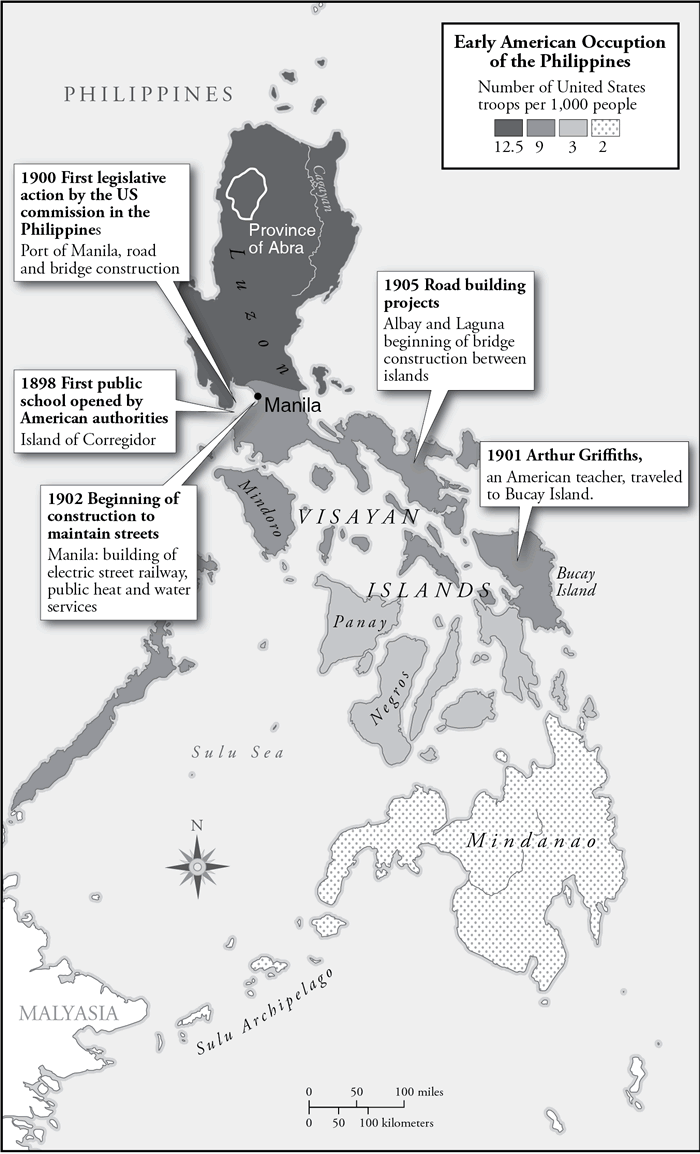

These are original maps made for the book 'Liberty's Surest Guardian.' The first map shows the location of the Philippines, surrounded by the expanding European and Japanese empires in the early 20th century. The second map is a more detailed overview of the Philippines, showing the density of U.S. forces in different regions, and some key events in the years after the removal of Spanish power. Copyright Jeremi Suri 2010.

click map to enlarge